I wouldn’t start from here

Why the new Scottish school behaviour guidance will change nothing, and help no one.

(I’ve been featured extensively in a new piece in this week’s Sunday Times Scotland. This is the piece I wrote that inspired the article.)

There’s new behaviour guidance out, designed to solve Scotland’s classroom behaviour crisis. Unfortunately, it isn’t very new, it doesn’t guide very well, and it won’t solve anything. Apart from that, I like it.

Crisis, what crisis? you might ask, and understandably so. Behaviour has been a huge issue for Scottish teachers for years, but no one is allowed to talk about it, literally. It’s been a guilty secret so taboo that publicly nobody wants to admit it, but in private no one denies. Scottish education is a monolith; it likes to mark its own jotters, and it closes up like a clam when attacked. Part of the identity of Scottish ed is the belief in its own exceptionalism, so when something makes it look bad, the default response has been to deny, deny, deny.

But that doesn’t work anymore, because the behaviour crisis has become so noisy as to be make it impossible to ignore. Teachers are striking over the chaos and lack of safety; news reports of attacks are distressingly common. Unions produce survey after survey, beating out the same mournful tattoo: we can’t deal with the behaviour we face. This was exactly the scenario in England a few years ago too, until the dams broke. Parents would be appalled if they knew what it was really like at the chalkface.

There has been a behaviour crisis in Scottish schools for years. So, dragged into a response like a teenager forced to write a thank you card, the Scottish government did what it does best: it launched a conference, which led to an enquiry, which commissioned a report, that made some recommendations, which has led us here. New guidance has, at last, been issued! A new document has dawned, let all the nations rejoice!

Jk it’s awful

But you can keep the party poppers in their box, because this guidance is an F-minus. It fails to understand what it’s like to run a challenging classroom or run a challenging school culture. And it also completely fails to understand the nature of school misbehaviour, and why children don’t always do what we want.

The reason that children misbehave is often because that’s what humans do when asked to do things we might not be inclined to do voluntarily, like think hard, do our best, or get along with others. Figuring out how to avoid that kind of effort is practically the factory setting of humanity.

Children are innately disposed to pursue their own desires and ambitions, just like regular people. The job of adults is to manage and direct their behaviour towards what is good for them, rather than what they deem pleasant.

In the absence of adult direction, children behave in all kinds of ways, not all of them useful, safe or productive. This is why we don’t allow them to drive tractors or get tattoos. Not because they are evil or stupid, but because they are human, and fledglings. Adults raise children into adulthood. The only children that do this by themselves are fictional. I can’t believe I even have to type this, so obviously axiomatic to human existence it seems.

But amazingly, this is still news in some quarters of education, many of whose inhabitants believe that children are naturally inclined to industry, altruism, and academic curiosity. (Rousseau is broadly blamed for this fantastical misunderstanding of the nature of students, a man who famously fathered five children and abandoned everyone to the orphanage. Real Dad of the Year there). To these people I ask: have you ever metany children?

Children as a cohort are a rich blend of kindness, selfishness, curiosity and carelessness, just like us, perhaps more so. It’s not that they all misbehave constantly- I would agree that most of them will usually behave, most of the time. It’s that all of them can misbehave some of the time, and some of them misbehave a lot of the time. And that, as Burke might say, is why we all have to agree to live by agreed systems of social conduct, protocols, etiquette, laws and expectations, Without them, life is chaos. Without them, classrooms are also chaotic.

I’ve worked for 15 years in the field of school behaviour and worked for 14 years before that in exclusively challenging, inner-city comprehensive secondaries. I’ve visited over 1400 schools in 19 countries worldwide, studying their systems and trying to discern what makes one school culture calm, and another clamorous. I’m also a Scot, living in Scotland. So it was with huge anticipation that I read the newly minted guidance for schools, Fostering a positive, inclusive and safe school environment.

Apart from that, Mrs Lincoln…

It's worth saying that the old guidance was also truly terrible. The most positive thing you could say about it was that it was short. Like, really short, a handful of pages. If you were a teacher wanting to know how to actually manage poor behaviour, you’d wonder if some pages had fallen out the middle, because there was no actual advice. Instead, readers were told to create welcoming spaces where every child felt involved and included but given no idea how this was to be achieved. You would be told to build relationships with your groups in order for them to access learning inclusively, but there wouldn’t be a crumb of actual direction about how to do any of that.

What you were told, over and over was that you had to be:

· Trauma informed

· Using restorative methods

· Inclusive

· Using a relational approach

· Following the principles of the United Nations Rights of the Child in everything that you did.

But you would have no training in how to do any of that. And if behaviour went sour then you would be advised to go back and look at those sentences again and think jolly hard about it all.

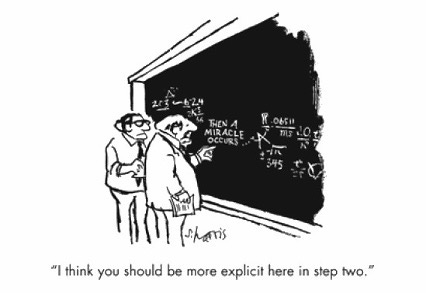

If you were a leader, it was the same and worse. The guidance for leaders was the same as for teachers: be trauma-informed, be inclusive, rights based etc. etc. this all sounds very lovely in principle. The only problem was it is completely useless advice. It was like telling a comedian ‘be funny,’ or a horse to ‘ride that bicycle’. The words might make a kind of sense but if you don’t know how to do it, you’ll never translate that onto practise. Platitudes don’t help professionals.

The inevitable result of all this was that behaviour in classrooms started to spiral out of control in Scotland. Because teachers, told to do three impossible things before breakfast, had no idea how to respond to misconduct or defiance. The crazy thing is that that most adults intuitively understand that children need at least three things from an adult in charge:

· Clear expectations

· Boundaries

· Consequences for crossing those boundaries.

There isn’t a society or community in the history of the world that didn’t depend on those principles. But teachers were required to somehow do,..what? It wasn’t remotely clear. I read the old guidance three times backwards and forwards and still couldn’t make sense of what it was you were expected to do.

And teachers agree with me. Every time I speak to anyone in a remotely challenging environment (i.e. almost every school) they say that their hands are tied; they don’t know how to deal with serious defiance or misconduct, but they’re not allowed to do anything sensible. Head teachers tell me that at their level things are just as bad, because the presumption of the Scottish government has been ‘no exclusions.’ Of course that’s not written down anywhere; it’s the culture of the system.

Heads have frequently told me that even when they need to suspend or exclude a student for violence or persistent chaotic behaviour, they are told by their local authorities not to do so, because it looks bad, or because they too have drunk the Kool Aid that believe that all children’s misbehaviour can be remedied by a nice chat and a kind word. But only someone who has never had to manage a challenging class could believe that this was realistic. And somehow, these people always end up writing behaviour guidance. Oh tempora.

The Behaviour in Scottish Schools Research (2023) found that staff believed there were no meaningful consequences for student misbehaviour; there was a perceived lack of support from Scottish local authorities to improve matters; and that there was a lack of confidence in leaders to support staff. You can only imagine how bad things have to have become for even that level of dissent to filter through the omerta of Scottish ed.

So to the new guidance; there is a tacit acceptance that what was previously available wasn’t enough. There was a lot riding on this: a chance to finally renew, to reboot the whole model of how we manage behaviour in Scotland. But it is a chance that has been utterly blown. It is a hunter’s stew of buzzwords and clichés about how children learn and behave. It simply takes the ingredients of previous incarnations of advice and reheats them in a longer and wordier form. It is an anagram of its predecessor.

There is strong impression that this guidance has been dragged out of the government, rather than freely offered. (‘We must be seen to be doing something’). It also has the strong aroma of a document with multiple parents, multiple voices, decided by committee. It resounds with the kind of advice a psychologist would give to a patient in therapy, rather than a practitioner’s guide how to run a classroom or school. Psychologists’ views are important of course, but this is like asking a particle physicist to cook a meal for Masterchef. It is often the wrong lens. Not all- or even most- behaviour stems from a deep-seated trauma, or psychological pathology. But this guidance would have you believe it. And if the diagnosis is wrong, the prescription will be too.

There is a lot here about consequences, but it isn’t the kind of discussion about consequences as most people understand them. There is a strong suggestion that consequences are certainly jolly important, and you get the sense that this really is the main purpose of the new guidance: to reassure everyone who mentioned consequences in the survey that they had been listened to.

It also makes a good deal of hay from the idea that consequences must be consistent in order to have an impact on school behaviour. Which is true. But then it goes on to describe how these consequences should vary from child to child, depending on their exact contexts. But you can’t have it both ways- you can’t personalise your every response to every separate incident of misbehaviour, and then claim that your system is consistent. This is like having a different speed limit on the motor way for every driver, depending on their individual circumstances.

Of course, we do (and should) have exceptions for every rule- emergency vehicles can disregard the highway speed limits to save a live, for example- but these exceptions must be exceptional. The authors of this guidance seem to have forgotten that if every response is boutique then you cannot claim that your system of consequences is consistent. It is literally the opposite. Teachers are making up their strategies on the spot, crushed by an impossible array of factors to consider. You would just give up.

The problem is that this forces teachers- already beleaguered and stressed by having to cope with thirty moving parts in the engine of heir classroom, to design personalised responses to every child’s misbehaviour. Every time, for example a student shouts out, or throws a pen at someone, the classroom teacher is expected to ponder on the student’s individual circumstances, his or her imagined needs, what they are trying to express by their behaviour, where the behaviour is coming from, what the United Nations thinks about child rights, whether the behaviour is an expression of some kind of repressed trauma, if the lesson is engaging enough for them, is the curriculum relevant enough, and on and on…and then think of the exact shape of the response that will remedy the behaviour and restore the student to an engaged and enthusiastic state. It’s exhausting. Worse, it’s impossible. It demands that teachers be telepathic, hypnotic detective-psychiatrists with magical powers.

Or you could just give the kid a detention and have them sent them out. But the guidance wouldn’t approve of that. There is no mention at all of how these consequences might be in any way centred around penalties, reprimands or sanctions. It skirts around the concept, but the implication is clear; penalties are not preferred. The whole section reads like someone was told that they must write about it, but they held their nose as they did so, before merrily returning to their favourite topics of unmet needs and therapy.

This allergy to any form of rebuke is central to the document. Staff must be mindful not to create any feelings of shame in children, in case they harbour some kind of trauma- as if serious trauma was something that every child carried. Fact check: they do not.

But children have misbehaved since children have existed. It’s practically in their job contract to push boundaries. How we respond when they do, indicates to them the meaningfulness of those boundaries. If kids mess about, then find that we do nothing, they learn that they can get away with it, and more. But if they find that violence, chaos or similar is met with challenge and deterrence, most will learn quickly to avoid repeating their actions.

The guidance is maddingly vague about what consequences means. It seems to mean lots of conversations with concerned adults who will attempt to patiently explain why punching someone in the playground isn’t kind. But such methods rarely work on any but the most conscientious children, the ones most liable to reflect on the impact of their actions with regret. But some children are very happy to accept what they have done, because they wanted to do it in the first place.

The new guidance also insists that school behaviour policies are designed in a collaborative way, involving the local community, parents, students and being sensitive to local circumstances, whatever that means. But why? Like most of this guidance it is riddled with these assumptions that one could only believe if no one ever challenged you to justify them.

There is a reason why we must have penalties as part of our behaviour systems, and why society has boundaries patrolled by them: because deterrence has a huge impact on social behaviour. Who do most people avoid parking on double yellow lines? Because of the desire to avoid the penalty. Why do most people slow down for traffic cameras? Same reason. Not everyone does, but that’s not the point- the point is that most people do, and that’s why we need them. If there were no penalty for poor driving, the roads would be a Mad Max hellscape. When you tell teachers that the only consequences they can use are highly complicated, drawn out, time consuming and ineffective, they simply won’t use them. And that’s what happens now in Scottish classrooms, as teachers simply start to give up under the demand placed on them.

Six impossible things before breakfast

Misbehaviour, in this report, is misunderstood as some kind of mad riddle that teachers have to decipher while teaching 29 other children number-bonds and phonics. Simultaneously they are expected to examine the student’s entire psyche, back story and socio-economic context like a forensic psychologist. Finally, they must do all this for a whole class, a hundred times a day. This isn’t just unrealistic, it’s crazy. Guidance you cannot follow will not be followed. It’s the opposite of advice. It’s ecivda.

But for me the reason this guidance is so, so bad, is that it pretends to be guidance, and it does so from a position of authority. It pretends to be an improvement to on what came before. But it is so incoherent, so nonsensical, so allergic to reality, that it simply obfuscates what school staff are supposed to do. And because it is an official document, it will drive the behaviours of thousands of staff and schools nationwide.

This was a golden moment to make things better, but it has been legendarily fluffed, punted over the bar and into the back row of the stadium. If a teacher in Scotland were to ask me how to use the new guidance to improve their classroom behaviour, I would, in the words of the Irishman who was asked the way to Dublin, say, ‘Well I wouldn’t start from here.’

Hi Stuart. Of course! Do so with my blessing. And if you would like me to speak, please get in touch. Either here, or at tombennettbehaviour@gmail.com.

Best wishes

Tom

I would like to reprint your excellent article in the Scottish Union for Education substack (with your permission). We are a group of academics, teachers and parents attempting to promote knowledge based education while challenging indoctrination in schools (and universities). As an aside, your Teacher Proof book is a breath of fresh air and describes much of what is happening in my university. We are organising a conference in an attempt to make education a key issue in the 2026 Scottish election (Nov 15th) and I was wondering if you would be interested in speaking? All the best, Stuart Waiton.