The thing I don't like has caused a bad thing

Strict schools, attendance problems, and the problem of thinking quickly but not carefully.

Up and down the country, attendance has dropped. Young people who once went regularly no longer see the point- or worse, they no longer feel welcome or included. Numbers are cratering, and where once it would have been unthinkable not to go, now it’s become, for many people, just normal. Perhaps worse, their parents are part of the problem; too don’t put pressure on their kids to go. Some of them also agree- it’s not where I want them to be either.

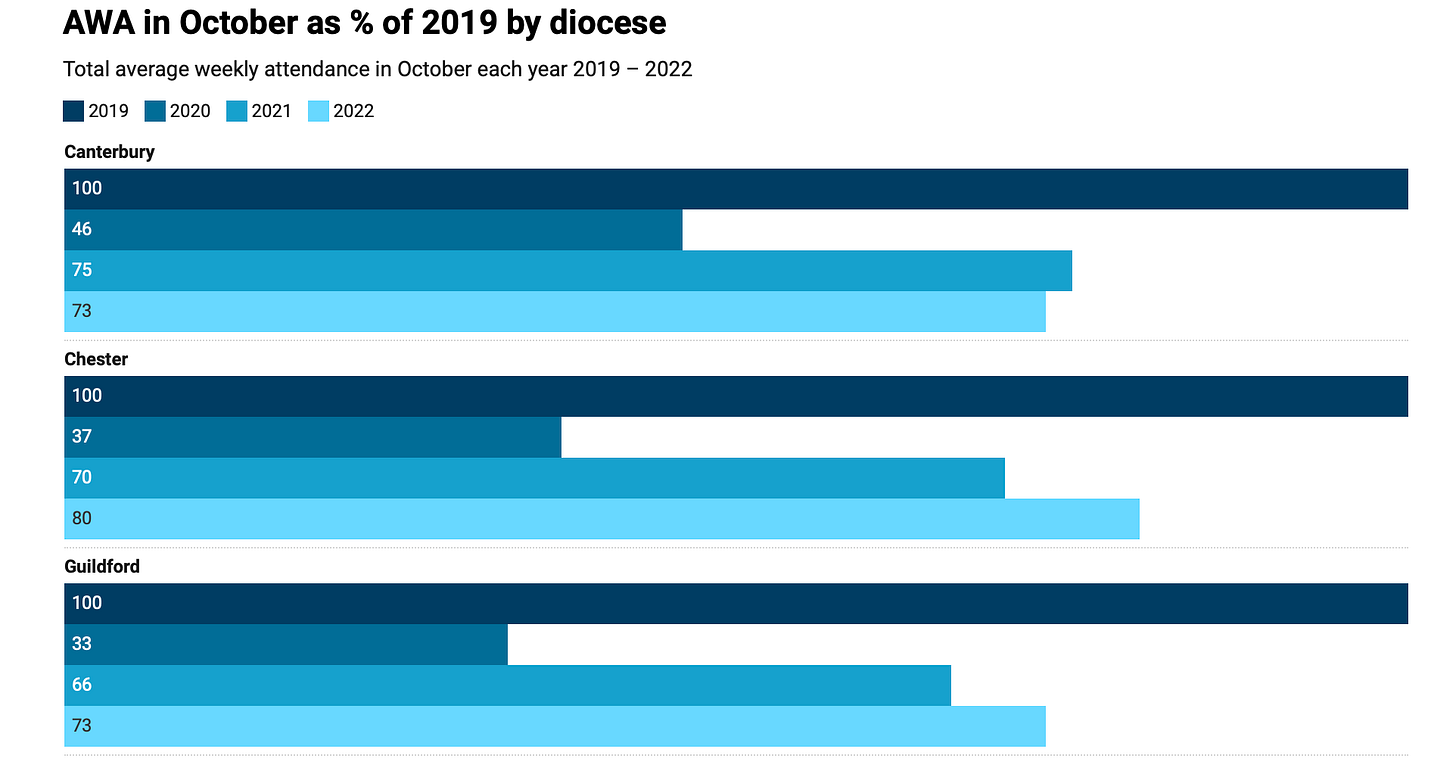

Schools? No, I’m talking about church attendance. Analysis by the Church of England has suggested that bums on pews have reduced by 80% since the pandemic. There has been a move to online, of course, but even that hasn’t offset overall numbers. It’s not just that some of the in-person attendees have moved to their laptops. It’s that lots of people have just stopped going/ attending/ logging in at all.

Of course, this is also part of a broader and longer trend of declining attendance over the past few decades in the UK. As society secularised, and as generations of adults with declining faith commitment raised their children, their burgeoning apathy was communicated to their offspring in the form of new habits and norms that deprioritised attendance, or other forms of commitment.

Even in this context, the decline after lockdown was stark. Numbers cratered during lockdown of course, because most churches were included in the general prohibitions associated with the strictest of lockdowns. But even when restrictions started to lift, attendance didn’t exactly rubber-band back to previous levels.

Lots of people who used to go to church were delighted to return, of course- church remains for many a place of great solace, community and belonging, as well as fulfilling spiritual functions.

But many did not. One does not have to delve too deeply to understand why. Many churches have demographics that lean heavily into the over 45s, who were particularly vulnerable to COVID. Setting aside the obvious possible impact of COVID on this demographics mortality rate, there was the broader issue of many feeling that it was no longer as safe as before to congregate in large numbers, in confined spaces. singing, shaking hands, sharing chalices, and so on. A deterrent factor was born.

But there is a bigger and broader factor: habits. Many people simply lost the habit of going to church. For many it had been a duty of assumption: once they simply went because it was the done thing in their communities. A lifetime of habit had created rail tracks of attendance that delivered them to church every Sunday, or days of obligation, or at the very least, the high festivals. Suddenly, not only did they not have to do this, they were told they couldn't. People found new things to do with their time. And lots of them got quite used to it.

So when doors re-opened, many peered through them, then back at their Sunday lunch, and made a decision. Of course, many tore back through the doors. But many did not. Life is a serious of choices we make, and many of them are based on what we value. And values change. Habits are hard things to build. They must be reinforced constantly, or they decline. And they can be replaced with new habits.

And that’s what we’ve seen, not just in churches in the UK, but in church attendance world wide. The global impact of COVID shook our habits like a snow globe, like a Magic 8-Ball, and the answer it returned for many was ‘Reply hazy, try again.’

What has this got to do with school attendance? Directly, nothing- church attendance hasn’t directly affected school attendance. But indirectly, everything, because school attendance and church attendance are excellent examples of something that has been affected by a third factor; COVID, and the lockdowns that this precipitated.

School attendance has also been hit in recent years.

The number of pupils missing the majority of school in England has doubled since the start of the pandemic, new data show.

More than 120,000 pupils were absent for half or more school sessions in 2021-22, according to figures published by the Department for Education on Thursday.

The number has doubled since 2018-19, when just more than 60,000 pupils missed half or more of school.

The research, which only includes state schools, suggests that around one in 60 children were absent for more than half the school week in the last academic year.

So we’ve seen a worrying decline in attendance at school, also after the pandemic.

This is deeply concerning. We know that student’s life success, in so many different ways, is positively impacted by school attendance, from average life earnings, to health, to academic achievement etc. Like punctuality, attendance is one of those foundational contributory factors. Perhaps obviously, but still worth saying, you have to be in your lessons to benefit from them.

Again, this isn’t just a UK phenomenon. Countries worldwide have reported similar levels of decline. Which supports the reasoning that COVID had a huge impact on the habit of attendance. For at last a year, many children were told not to come in. Their parents had to adjust to this new normal. They got used to it. Just like churches.

So we have a clear, fairly strong idea of at least one huge factor behind the decline in large national institutions that traditionally relied on face-to-face attendance. It plays out in a thousand different ways in a thousand different sectors, all of which are also interesting and relevant and worthy of study, but to ignore this main one is plainly insane.

Which is why it’s bizarre how many people, witnessing this decline, have leapt on almost anything else as the main contributory reason. The chief factor in their deliberation appears to be ‘is there something I don’t like? Then it must be the reason this bad thing has happened.’ I’ve recently read that silent corridors are the reason why attendance is in decline. Others have blamed suspension and exclusion policies. Some say it’s because schools don’t do enough for students’ mental health. Others say it’s because the curriculum is no longer relevant to children in a 21st century where students will grow up to do jobs that haven’t been invented yet, etc etc. All the old saws. All the things they already hated about education.

New thing proves thing I already thought

This is a re-invention of the old adage that when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When you are so wedded to your one lens, everything you see is understood through that lens. For some it’s power; others, oppression, or class, or status, or wherever their ideology leads them. But this confirmation bias is fatal to reason, because it denies any evidence that contradicts it, or worse, converts it into more reasons to believe whatever one already believed. For the faithful, all acts are acts of God; even contradictory ones are viewed as cryptic trials of faith. Like a Millennial Apocalypse Cult surprised by waking up the day after Doomsday, and deciding they must have got the date wrong.

The reason why so many of these positions are faith positions is because they aren’t backed by reason but by, apparently, a voice inside their exponents heads. We have no evidence to suggest that there is a connection between silent transitions (whatever you think of them) and attendance, or mental health, or being made to turn up to lessons on time. It’s just something the critic already didn't like. So it must be the reason. Which is exactly the reasoning that the racist applies to their own economic misfortune- it must be immigration that caused it. What else could it be?

It seems- and I admit this with reluctance- that there are a lot of people out there who really have a problem with expecting kids to behave sensibly in a school environment. Who feel, for whatever internal psychological reason, that all rules are oppression, and that all expectations to try hard beyond one’s own desires, are tyrannical. Granted most of these people have never had to manage a challenging class successfully, but why let wisdom or experience stand in the way of one’s piety?

Children flourish best in an environment that is safe, calm and predictable, and where they feel valued. That is the literal definition of an environment run on compassionate boundaries, clear, taught expectations, support for those who need it, and consistent, predictable consequences. There is no other way to square this circle. That is the environment where even- or especially- the most vulnerable flourish. But it is a rising tide that lifts all ships. All children (and staff) benefit from this structure.

In our efforts to demonstrate how deeply we care about children, let’s not sacrifice them to our own biases, and desperation to appear compassionate. Children obviously deserve better.